Buddhism, Science, Life and Modernization — A Conversation with Professor van der Veer

This dialogue recognizes that Buddhism, with its rationality and empiricist approaches, is increasingly recognized as a science and philosophy, rather than merely a religion. Also discussed are gender equality, the uniqueness of Tibetan Buddhism, and the engagement with modernity and materialism while trying to preserve Tibet’s own cultural and spiritual lineage.

“We can say that Buddhism blends together religion and philosophy into a single entity; as such, it is defined as a science of education.”

To Step out of or to Walk into the Secular World?

Where the Uniqueness of Tibetan Buddhism Lies?

Professor van der Veer: I would like to start with a question concerning Tibetan Buddhism. I understand that Buddhism will exhibit certain characteristics as a result of having sprung up in a particular environment. For instance, Buddhism in Tibet has taken on Tibetan cultural characteristics. My question is, how does Tibetan Buddhism relate to forms of Buddhism that have grown up in China? Is there something specific that Tibetan Buddhism offers within the context of the Chinese environment that other forms of Buddhism do not?

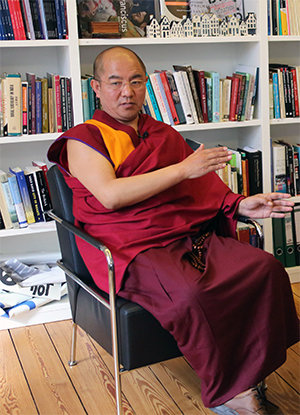

Khenpo Sodargye: To answer your first question, Buddhism originated in India and when it spread to the Han Chinese area, it integrated with Chinese culture and became what we think of as Chinese Buddhism. Similarly, it entered into Tibet about 1300 years ago and was integrated with Tibetan culture and became Tibetan Buddhism.

Generally speaking, there are no big differences between the two and each share the same idea that the Dharma guides us towards the attainment of buddhahood and directs us to show love and compassion toward all sentient beings. So, in terms of general principles, there is no difference. However, in many Tibetan Buddhist lineages, it is very common to resolve the meaning of specific points of Dharma through debate; this is a very popular component of Tibetan Buddhism that is not found in Han Buddhism. Putting great emphasis on theories and the exploration of theories, is also quite unique to Tibetan Buddhism, and is a primary factor that differentiates it from other schools, and Han Buddhism in particular. So Tibetan Buddhism offers a special advantage when it comes to theoretical study.

Buddhism, A Religion and A Philosophy

Professor van der Veer: We in the West, tend to use the word religion very casually. We say Buddhism is a religion, Christianity is a religion, Islam is a religion, and so forth. Some people though, argue that Buddhism should be classified as a philosophy because the gods do not occupy any importance in it. What is your position on this question?

Khenpo Sodargye: Buddhism is indeed one of the four greatest religions of the world; it’s unreasonable to say it’s not a religion, as it obviously has its own rituals, ceremonies and monastic class. In fact, it contains many levels of monastics with various kinds of religious apparel that identifies them.

But, I think it is also a philosophy, something more than a religious ideology or a simple set of worldly ideals created by people’s imaginations. I have been studying Buddhism for a long time and, it seems to me that we can say Buddhism is encyclopedic. For example, in the Tibetan Buddhist literature alone, we find writings on astronomy, geography, anthropology, sociology, psychology and so on. Tibetan Buddhism not only provides theories on these subjects, but it offers profound discoveries and explorations into the nature of our world in many other areas, as well. As such, regardless of the many strange things that happen in this world, I personally, am not in the least bit surprised because Buddhism has already given me specific explanations for these types of occurrences.

Therefore, I think it’s both a religion and a philosophy. Buddhism is not restricted to what we see in a certain confined context or from a narrow perspective. Buddhism is not merely a ritualized religion nor is it a pure philosophy like those of ancient Greece or of certain narrow-minded forms of oriental thinking. We can say that Buddhism blends together religion and philosophy into a single entity; as such, it is defined as a science of education.

Engaged Buddhism: a Loss of Tradition or A Successful Adaption?

Professor van der Veer: I would also like to discuss the question of Buddhism and modernity. In China, there was a famous Buddhist leader, Tai Hsu, who tried to develop engaged Buddhism, and in Sri Lanka, Anagarika Dharmapala basically did the same thing. From what I understand, you also are in favor of a modern, engaged form of Buddhism. What tradition in Tibetan Buddhism promotes this idea of a modern Buddhism and are there Buddhist leaders that are critical of this idea?

Khenpo Sodargye: I think that there are two aspects of Buddhism that should be understood and propagated. On the one hand, there are traditional, profound and authentic principles that cannot be changed to suit the times or to fit into current trends. Some people today know little about the profound teaching, practice and realization in Buddhism, but they judge Buddhism with purely secular opinions and attempt to explain it through their shallow understanding. I don’t agree with this kind of secularization and modernization, as Buddhism itself is very profound. Nevertheless, worldly people try to explain with shallow words something that is beyond their understanding. On the other hand, Buddhism should be included within the context of worldly life, meaning that the idea of engaged Buddhism should be applied to Buddhism as a whole.

Speaking of engaged Buddhism, nearly 100 years ago, Master Tai Hsu, along with Master Fazun, befriended many Tibetan masters. In his book, Professor Gray Tuttle discussed the relationship between Master Tai Hsu and Tibetan Buddhism and describes how he promoted engaged Buddhism in the Han area of China in the 1920’s and 1930’s.

I myself acknowledge the traditions of engaged Buddhism, but feel strongly that it needs to be based on authentic Buddhist teaching. Actually, there is a solid basis for the promotion of a Buddhist engagement with modern life, through the doing of good deeds and the avoidance of all bad ones and also engaging in virtuous thoughts and actions to improve our morality and purify our minds. This is theory and action worth promoting.

As an example, I have built primary and high schools in remote areas, organized Buddhists to offer help in disaster-stricken areas when needed, and also provided financial support to poor students. So far, I have been able to help over 370 students, including 200 Tibetan college students, through the establishment of a foundation to promote education under the guidance of Buddhist concepts. I believe that modernization and secularization are necessary for the development of Buddhism in this day and age.

In many ways, it is easier to promote Buddhism in the Tibetan areas than in the Chinese areas because most Tibetans have had Buddhist traditions integrated into every aspect of their life, since their childhood. For them, Buddhism is not just a religion but also a daily part of their lives.

To Step out of or to Walk into the Secular World?

Professor van der Veer: I feel, in a practical sense, that it is difficult to make this distinction. Following the precepts of canonical Buddhism, the Buddha required people to step out of the world, to live in a monastery, to meditate and to perform rituals in order to come to a pure state of mind, whereas engaging, as you are now engaging with me, travelling through the world and spreading your message, is disrupting to the monastic practice, the practice of meditation and so on. So where is the boundary? How can you do canonical Buddhism while still interacting with modern society? It seems that this not an easy thing to do.

Khenpo Sodargye: Actually, we can interpret the tradition in two ways. The first is the external tradition, like monastics living inside temples, wearing monastic clothing, engaging in various Buddhist rituals and so on. Personally, I believe it is good to practice all these traditions within the temples. The external form actually embodies the internal culture. As Confucius said, once we forget etiquette, the cultural meaning within it will be lost too. Therefore, I don’t think it is necessary to abandon monastic traditions.

More importantly, however, it is the internal tradition that represents the most profound meaning of Buddhism. If these profound meanings were to be expressed only through shallow ideas that have sprung up during current times, I am doubtful that Buddhism would remain compatible with the world. However, if we turn our attention to society, and walk into a crowded shopping mall for the purpose of spreading Buddhism, such activity would be a demonstration of the Buddhist spirit that emphasizes being of benefit to sentient beings. Whether they are monastics or lay practitioners, anyone can spread such concepts to his or her community. This is not only true in in modern times. At the time of the Buddha, the Buddha asked his disciples to go to various places like brothels and palaces to spread the Dharma. This is actually a kind of ideology and a way of teaching.

In these terms, I think if secularized Buddhism in today’s society can keep the original Buddhist meaning, there will be no contradiction. Without abandoning the traditional rituals, Buddhism can still fit completely into today’s world and into the values of every single person.

I myself acknowledge the traditions of engaged Buddhism, but feel strongly that it needs to be based on authentic Buddhist teaching. Actually, there is a solid basis for the promotion of a Buddhist engagement with modern life, through the doing of good deeds and the avoidance of all bad ones and also engaging in virtuous thoughts and actions to improve our morality and purify our minds. This is theory and action worth promoting.

Gender Equality: Tibetan Buddhism Agrees with the Modern View

Facing Modernization: to Surf the Wave but Not Sink into The Ocean

Professor van der Veer: So, my next question is, what is the relationship between Buddhism and modernity? Many religions like Christianity, Islam and others reject parts of modernity because they want to protect traditional ways of thinking and ways of life, which they feel are threatened by a modern secular world. What aspects of modern society or modern life does Tibetan Buddhism reject?

Khenpo Sodargye: Since religions exist in different ages, during which people’s habit patterns, lifestyle and preferences are constantly changing, Buddhism or any other religion must adapt to the society in which it finds itself, otherwise, it would be difficult to sustain as society changes and evolves over time.

Within Tibetan Buddhist texts, there are extremely detailed explorations of the truth of all phenomena—these truths are ultimately unalterable. As such, I’m not worried that the development of science might destroy the principle meanings of the Buddhist scriptures. However, we should be aware that some Buddhists, may easily become lost when using such modern approaches as the Internet to follow and practice the Dharma, even though these are great tools that can be used to promote Buddhism in the modern age.

In this light, I think there are different types of people in the world of Tibetan Buddhism. The first type is very conservative: these people rarely know about modern science and technology and other such things in the outside world.

People of the second type, most part, retain their original Buddhist traditions but also keep an eye open to contemporary ideas and values, including various theories and views from the realm of western science, which they then consider and compare with what they know of the Buddhist teachings.

People of the third type, don’t care about the original traditions and pursue romantic notions of modern western culture, which through over secularization has already lost the original teachings of Buddhism. There are even some monastics in Tibetan Buddhism who feel that Dharma practice is not meaningful to their lives and prefer to pursue aspects of western culture, choosing instead to become teachers in secular schools, for instance.

Among these three types of people, I think I am of the second type, I not only follow traditional culture and the seeking of ancient wisdom, but I also pay attention to current trends and ideas in western and eastern countries. I believe we should neither be too conservative nor too secular, and there should be a path of integration that fits both contemporary and traditional principles. I like the modern world approach very much, but I also take the traditions of ancient culture quite seriously.

Balance: Spiritual World or Material life?

Professor van der Veer: Since the 19th century, the modern world seems to be divided between two major modern ideologies: liberalism, which is the basis of capitalism; and socialism, which is the basis of the People’s Republic of China, the Republic of Vietnam, and so on. From a religious point of view, ie: The Catholic or Islamic point of view, these new ideologies are rejected and are seen as materialistic, as being focused only on money and the material aspects of life. How does Tibetan Buddhism relate to these modern philosophies?

Khenpo Sodargye: Speaking of liberalism, actually the Buddha said in a sutra that its spirit of liberty and equality is the primary source of all happiness. Therefore, whether in a capitalist or socialist context, enjoying the basic right to the freedom of thought is very important and deserves protection. On the other hand, in the Buddhist teachings, we have a bottom line moral standard, which, if crossed, will throw people into a chaotic state. As was once said, “too much freedom will lead people to an aimless life.”

Generally speaking, according to Tibetan Buddhism, we need to pay equal attention to both material and spiritual development. First and foremost, our spiritual happiness and inner contentment have great importance; without them our lives would be very difficult, no matter how abundant our wealth and possessions. Secondly, the external material aspects are also important; since we can’t live solely on spirit; we need material resources as a support for surviving and being in the world.

Tibetan Buddhism does not advocate focusing on one side or the other, but rather emphasizes finding a balance between the material and spiritual aspects of our lives. Therefore, we shouldn’t lean to either side because that won’t help us bring benefit to our lives, which is the foundational ideology underlying Tibetan Buddhist culture.

As a Tibetan Buddhist, I am concerned about all the related knowledge of the inner heart and its significance. At the same time, I also care about the benefits and shortcomings that a material focus has brought to human society. Followers of Tibetan Buddhism may be experiencing any number of different life situations, as is also the case for followers of Catholicism or Christianity. There are traditional people who engage in their own practices in remote mountain villages and reject anything to do with the outside world. In contrast to this, there are those who live in cities and desperately pursue a materialistic life and completely neglect the spiritual world; this has become quite a common phenomenon in the modern era. Indeed, regardless of our situation, we should strive to maintain a reasonable balance between our inner and outer realities.

Gender Equality: Tibetan Buddhism Agrees with the Modern View

Professor van der Veer: One aspect of the many modern ways of thinking concerns gender equality. The traditional way of thinking is that there is a fundamental difference between men and women, as well as a social hierarchy that places men higher than women. In Indian monastic traditions, such as the Hindu mönch, women are not allowed to become nuns, which is contrary to these modern ideas of gender equality. What is the Tibetan view of the role of men and women both in religious practice and in religious organizations?

Khenpo Sodargye: Tibetan Buddhism includes both the Mahayana and the Hinayana traditions, within which can be found great complementarity and unity. So, in my opinion, the idea of equality in Tibetan Buddhism is very well suited to the progressive values of many modern people.

For example, in terms of monastics, both men and women are allowed to be ordained. It’s true that there are more precepts for women (Bhikkshunis) than there are for men (Bhikkshus). But there are understandable reasons for that. In a general sense, women are the same as men, but it seems to me that, in some cases, they may more easily become emotional.

Aside from this, men and women are treated equally in Buddhism. Additionally, in terms of seeking happiness and avoiding suffering, all sentient beings are completely equal because they all share the same feelings. In this regard, Buddhism teaches complete equality.

Of course, such equality does not mean that all Buddhists are exactly the same, because men and women have different capacities and predilections. Men and women exhibit different abilities; this is true not only among Buddhists, but among all people in the world. If we look around the world, we can notice the fact that, men and women make different contributions to the world.

In conclusion, Buddhism undoubtedly advocates equality between men and women, and that is a basic teaching of the original Buddhism. Tibetan Buddhism, as another version of Indian Buddhism, certainly follows the same rules.

Professor van der Veer: In India, the emphasis in the monastic tradition is that women have a reproductive function and actually cannot engage in meditative practice. And I think, to be honest, in Buddhism there was a long period of time in which nunneries were a rather marginal phenomenon. The increase in the number of nuns is a relatively modern phenomenon. So, I’m still not entirely convinced that there is true belief in the equality of men and women in Buddhism. In India, there is no idea of gender equality, instead there is the idea of gender hierarchy. Quite clearly, it is the same in Catholicism, Islam, and all other major traditions. So, I would like to hear a little bit more about your idea of gender hierarchy, as it exists in Buddhism.

Khenpo Sodargye: I believe there should be no inequality in Buddhism. Take our Buddhist Academy, for example. There are about 2,000 monks and 4,000 nuns officially registered and approved by the government. Among Chinese Buddhists, women also account for a greater number than men. For lay practitioners, men and women are equally able to take precepts. In the Buddhist teachings, we do not see any discrimination or scorn for women nor is there anything that is particularly not allowed for women.

However, for some groups of people or in certain sectors of society, including in Tibet, because of local traditions, reality may end up with another story. In the past, Tibetan men were in a dominant position and held more power in the family; women were treated as the weaker sex and so were generally held to be subservient to men. Although they were all Buddhists, this phenomenon came from the tradition of Tibetan society rather than from any Buddhist tradition.

The idea of gender equality arose out of modern society and may have arisen from the ideas of certain individuals or from the ethics of certain traditions. It is definitely a necessity of the present era that we should further enhance this idea by modernizing religion. As I have said, in the Buddhist teachings, there is no discrimination or unequal treatment for women. There may be some specific descriptions of some individual women who received unequal treatment, but these anecdotal stories should not be used to imply that inequality exists within the teachings of Buddhism.

Science and Religion: Related or Divided?

Professor van der Veer: Now I’d like to discuss the relationship between Buddhism and science. The major religious traditions in the 19th century have abandoned the claim of producing scientific knowledge. Knowledge is produced in universities and in laboratories, such as here at the Max Planck Society. Religions now concern themselves with providing moral knowledge or a kind of moral radar to help people act appropriately in the world. So there now exists, this division between knowledge and morality. I wonder to what extent Tibetan Buddhism follows the trend of abandoning the idea that religion actually provides knowledge about nature.

Khenpo Sodargye: Personally, I am very interested in the relationship between modern science and Buddhism. I once wrote a book about science and Buddhism, in which I specifically discussed Buddhist views and various ideas and conceptions of modern science that had contributed to human society.

As a Tibetan Buddhist, I acknowledge all the inventions and the truths discovered through the efforts of scientists since the 19th century. I also think that scientific researchers should not deny all the truths that are claimed by religion, most of which align with science.

Take the almanac calculations in Tibetan Buddhism, for example. Without any scientific instruments, we can create a calendar of precise accuracy. To serve in this capacity, we have a special astronomy group of six members in our academy, who don’t use any scientific instruments; it takes them about two months to calculate a calendar by using the method provided in the Kalachakra that includes for a given year all the solar and lunar eclipses as well as the weather conditions. This tradition continues to be handed down in our academy. So, I believe there continues to exist some mysterious relation between the various sciences and religion.

The View of Buddhism Concerning the Morality Aspect of Science

Professor van der Veer: Are there any aspects of modern science that you would reject as being foreign to your tradition? As we are all aware, there are a wide range of scientific discoveries and experiments that are rejected by various religious traditions. One example is the use of embryos for genetic engineering, which has become a major moral issue for a number of religions. In Tibetan Buddhism, is there opposition to these kinds of scientific experimentation?

Khenpo Sodargye: From the Buddhist point of view, some of the negative ways that modernization has impacted human society really worry us. We believe, for instance, that for all sentient beings, regardless of whether they are human or animal, life is equally precious. Therefore, dissecting animals, or the direct killing of animals such as insects in farming practices, or the use of science and technology to invent destructive machines designed to more efficiently slaughter animals, are all negative actions that we, as fellow sentient beings, need to abstain from.

Nowadays, human beings are facing many grave threats, such as that of nuclear war. In fact, the root cause of these kinds of crises exists within people themselves. It is somehow ironic that all the sophisticated intelligence of the world’s greatest scientists may, in the end, cause widespread destruction to the entire human species. If we look back at history, we can see that World War II caused great harm to the entire world, but if something similar were to happen again, at a time of even more advanced technologies in the hands of somebody with the desire for global domination, it would be even worse and could cause indescribable damage not only to the people of this earth, but to the earth itself.

So, in Tibetan Buddhism, there are such principles that we do not approve of, such as any invention, even if it does come from the scientific world, that would be intended to take life or that causes harm to living beings,

The idea of gender equality arose out of modern society and may have arisen from the ideas of certain individuals or from the ethics of certain traditions. As I have said, in the Buddhist teachings, there is no discrimination or unequal treatment for women. There may be some specific descriptions of some individual women who received unequal treatment, but these anecdotal stories should not be used to imply that inequality exists within the teachings of Buddhism.

The Necessity of Cultural Diversity on This Planet

A Country of Nobel Laureates: the Integrated Power of Science and Culture

Khenpo Sodargye: I noticed that there are many people in Göttingen who have won the Nobel Prize, this in comparison to other countries or regions where there have been far fewer. So, I am wondering, why, in such a small place, have so many people become Nobel laureates?

Professor van der Veer: I think the reason is that Germany was the first modern industrial nation in the world. By the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century it was really the most progressive, modern industrial nation on the planet. German culture has always emphasized science and knowledge, and today there is still an enormous amount of cultural respect for professors and for the whole idea of science. Therefore, the material progress of Germany and the cultural emphasis on knowledge form a major element within the German culture.

Germany: Does Geographic Condition Contribute To Human Wisdom?

Khenpo Sodargye: But Germany is not the only place with a cultural respect for knowledge and a place at the forefront of the Industrial Revolution. So, I am still wondering what kind of buildup in such a short time leads to so many Nobel laureates. Can it be that it is mainly due to the respect for knowledge? To me, it seems that human wisdom doesn’t result from the praise of others. I wonder if it has something to do with the geographic condition of this place, which is also a common consideration in China.

Professor van der Veer: I think this particular idea was pretty much what Germans call “culture” or “kultur”, which describes people who live in a particular kind of ecology and create a kind of language and a set of habits. So, from Hegel and Fichte, from these philosophers onwards, there’s a kind of idea of the relationship between the landscape and the culture, which would be very close to your way of thinking.

But the fact of the matter is that Germany also created two world wars and that after World War II, this particular place was no longer as it had been. It moved somewhere else, to Harvard, Stanford, and other places in the United States, the ecologies of which are actually very different from Göttingen. I believe that it doesn’t really matter that much where ideas come from.

Khenpo Sodargye: Generally speaking, scientists acknowledge the value of objectivity through questioning and research that is conducted in an objective and measured manner. So, if one is a scientist, one treats objectivity as a core value. From the Buddhist or religious point of view, however, it is not only objectivity that is important in the world, in fact, subjectivity is considered to be of equal importance. As we can see in our daily lives, it is quite a common phenomenon to find that many issues cannot be solved or explained in an objective manner. What’s your opinion on this?

Professor van der Veer: I think that for the humanities and in my area of the social sciences, there is the same kind of combination of objectivity and subjectivity, as is propounded by Tibetan Buddhism. In the idea that one tries to find knowledge and data that can also be seen by others, there is a kind of need to universalize or generalize what one finds.

But in anthropology this is always related to the observer, and so there’s always a subjective element inherent in it. One of the main issues in the social sciences is to try to develop methods that are truly objective even though there is no particular discipline that can define that. Psychology and sociology have been more successful in developing objective criteria for study, but in my case, we are closer to other forms of knowledge in the sense that we utilize a combination of the subjective and the objective.

The Necessity of Cultural Diversity on This Planet

Khenpo Sodargye: As a Tibetan Buddhist, I also seek to learn about Han Buddhism and many other religions, but I feel a strong attachment to Tibetan culture and Tibetan Buddhism because I believe that they represent a great treasury of thought for all humankind. However, there are many people, including some Tibetan youth, who do not appreciate their precious value. Many young Tibetans abandon their own culture and religion and go to seek other cultures or knowledge, believing that this is a wise decision.

So, I want to ask, what is your opinion of Tibetan Buddhism? What kind of expectations would you have of young Tibetans? Even if this isn’t your field of research, as a social scientist, what’s your opinion in general? Do you have any advice for the youth of Tibet?

Professor van der Veer: I think we can generally say that this is a question about the necessity of diversity. Mankind needs to explore different forms of life and different ways of living, in order to find solutions for a whole range of problems, many of which we are not even aware of yet. A biologist will say that diversity in the realms of plants and animals is actually necessary for the survival or the continuation of the world. A social scientist or human scientist will say that the diversity of cultures is an absolutely necessity, if we are going to be able to understand different ways of responding to problems that we know of now and for those problems that may potentially appear in the future.

So, maintaining cultural diversity is very important, so that everything does not become the same. Everyone wearing the same T-shirts, watching the same television programs, driving the same cars, going to work in the same factories, and so on. Some of these things are inevitable, and of course, elements of the major economic systems will spread to all parts of the world.

But we’re now speaking about culture and religion, and the diversity of culture and religion is indeed good. In that sense, Germans want to keep their own heritage, the French want to keep their own heritage, and the Tibetans should invest in keeping their own heritage. I think, from an objective point of view, we are all in the same boat. How do we maintain our own traditions while still contributing to a more universal heritage.

Shanghai: a Lost Religious Site?

Khenpo Sodargye: I know that in many universities and in various religious studies all around the world, you have played an important role and I rejoice in the many great contributions you have made to the world. I noticed that in Shanghai, you are carrying out some research projects on urban religious diversity. I am wondering what the main purpose of this project is, how you are progressing and what drives you to perform research on this subject?

Professor van der Veer: The specific problem that interested me in Shanghai is that, before 1949, Shanghai was an important center for Chinese religions such as Buddhism and Daoism. In the years leading up to 1949, you would have found temples and shrines and religious practices taking place all over the town, along with ancestral houses around which religious communities, were based. But now that has all changed and these days, it is very hard to find public displays of religion in Shanghai.

So, my research revolves around the question of what led to this change. Furthermore, the question becomes more interesting by the fact that Shanghai has now been open for the last 20 or 30 years, and because it has been more open for immigration, it has been growing very quickly. Many people come to Shanghai from other areas of China, and also from your area, and bring their practices to Shanghai. So where are these practices taking place? That is actually the simple question we are trying to find the answers to. How are people continuing their religious practice in a new environment in which you cannot publicly display it.

Looking Forward: Dialogues Between Science and Religion Are Meaningful

Khenpo Sodargye: Yes, I believe the diversity of religious culture is very important. There are so many kinds of religion in the world and their history is so rich.

Do the Max Planck Institutes have any research projects directly related to Buddhism, even if it is not necessarily Tibetan Buddhism? Has Buddhism been part of your research or do you have any plans for upcoming projects in this area?

Professor van der Veer: We do now have a project on Taiwanese Buddhism, specifically on the Tzu Chi Foundation and its activities in China. I would be very much in favor of doing more research on Buddhism since I think that currently, there is too much research emphasis on Christianity in China. Christianity is seen as a problem in China and therefore there’s more research on it. Conversely, Buddhism is not seen as a problem, therefore there’s little research on it.

I would find it very interesting to learn more about Tibetan Buddhism, and specifically, how you and your organization might expand and get more people following you in China. So, I would be very much in favor of a project to study your efforts in Shanghai or Beijing, or in other places, and engage with people who want to become Buddhist, or with the Chinese in general, and how that all works. But it always needs to have the support of the government to create these sorts of studies.

Khenpo Sodargye: Many Dharma masters in our Buddhist Academy, including myself, and others, like Khenpo Tsultrim Lodrö, are all very interested in science. We have studied Tibetan Buddhism and Chinese Buddhism for more than 20 years, and we would like to exchange our ideas more often with academic people if there is such an opportunity in the future.

In the realm of Buddhism, whether we are talking about Tibet or in Mainland China, our Buddhist Academy is well respected by representatives of the many different schools in Buddhism. However, in fields of science such as sociology and anthropology, we have very limited knowledge. Khenpo Tsultrim Lodrö has been carrying on research for almost 20 years and has written quite a few books, as have I, but we have had little chance to engage in discussions with scientists face to face.

We have met a lot of domestic scientists in Beijing and in many other places in China. If circumstances allow it, we would like to continue to have more dialogues with scientists both at home and abroad, because we are interested in the essential wisdom of the social sciences and religion, both of which embody precious knowledge for human society. There may be some conflicts or differences between them, but I believe through continued dialogues and discussions there is much that we should be able to learn from each other.

Professor van der Veer: I would be very much in favor of that. I personally would very much enjoy visiting the Academy, both to give lectures and to have conversational exchanges with various people there. I would also like to see how Buddhism is developing in China. So, I think we have a great deal of common ground and I would enjoy continuing to create collaboration in these areas.

Thank you again for coming and for having this conversation with me. It’s always a pleasure to see you, because you are a person who has humor and the grace of a good laugh, and at the same time, you are someone who is thinking deeply about all kinds of problems. It has truly been a pleasure to have you here.

Buddhism is not restricted to what we see in a certain confined context or from a narrow perspective. Buddhism is not merely a ritualized religion nor is it a pure philosophy like those of ancient Greece or of certain narrow-minded forms of oriental thinking. We can say that Buddhism blends together religion and philosophy into a single entity; as such, it is defined as a science of education.